What can happen in one part of the country, in one city, can spread across the national stage and even round the world. A movement expands on what individuals and groups can do. The civil rights movement and the labor movement happened in cities across the nation for decades. Labor organizing has origins dating back to the 1800’s, however the labor movement experienced a high level of momentum during some of the same times as the Civil Rights Movement which lasted from the 1940’s through the 1960’s. Those movements have unique ties and roots in Detroit, and the civic action that occurred in our city influenced the movement as a whole.

Organized Labor in Detroit

It is very likely that you’ve heard the phrase problem solving used across many situations and contexts. To problem solve is to use the tools of critical thinking to examine, and then, address something that needs repair, reassessment, or even rebuilding. From a historical/cultural perspective the advancement of cultures and nations were built on successful problem solving and cooperation across groups of people.

The labor movement in Detroit’s goal in the late 1940’s through the 1960’s was to problem-solve the issues experienced by blue collar workers. Issues like:

| Wages | Workers would be paid very little money for long hours of often dangerous work. |

| Work Hours | Workers would be required to work long days without time off. |

| Work Environment | Workers would be required to do dangerous work, work in dirty environments, and/or work without access to spaces like lunchrooms or bathrooms. |

| Work Discrimination | Workers would be assigned work and treated differently based upon race, gender, and national origins. Women and people of color would be paid less and assigned more challenging jobs. |

As an industrial city, Detroit’s ties to the labor movement are deep. Detroit had been manufacturing for years ahead of automobile production–from stoves to rubber for tires. Detroit’s connection to transportation and wheels had already been present as well. Bicycle development and paddy wagons lead the way for automobile companies in our city. The start of Ford Motor Company, the growth of car manufacturing in the city, and Ford’s offer of a $5 per day wage (in 1914) led to a large percentage of Detroit’s population being employed at these factories over time. That same infrastructure made Detroit an ideal place for manufacturing war materials during World War II which created another growth of job opportunities and new residents seeking them. The owners of these companies grew to be very wealthy and had influence over the development of Detroit’s community. The jobs provided also opened opportunities for workers to grow wealth however, at a much lower scale than the company owners and with many more dangers. For this reason the need for organizing was felt widespread.

Detroit’s labor movement has a strong connection to the national stage through:

- The presence of automobile plants facilitated the growth of the United Auto Workers (UAW) and its influence

- Key labor figures have roots in Detroit and/or work that influenced labor organizing in other cities

- Its connection to racial justice organizing given the demographic make up and segregation tensions of the city

We’ll look at each of these in the following sections.

The Power of the United Auto Workers

News of Southeast Michigan autoworkers’ fight to obtain higher wages and better working conditions spread across the country, at a time when coverage of the movement and its potential impact on public opinion was critical. The National Labor Relations Act, also known as the Wagner Act, was passed in 1935 and challenged in the Supreme Court that same year. At the same time, during the 1930’s and 1940’s, the rise of autoworkers in Detroit and Flint was growing in its notoriety.

The National Labor Relations Act was signed into law by President Franklin Roosevelt on July 5, 1935. The law addressed the relationship between unions and employers in the private sector, and guaranteed the rights of employees in the private sector to collectively bargain and take collective action. It established the National Labor Relations Board which is a federal agency that’s responsible for enforcing labor laws which protect workers’ rights to participate in unions and prevent employers from engaging in unfair labor practices.

Shortly thereafter, the law was challenged in the Supreme Court by Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation which had fired employees for joining a steel workers union. At the time that the court was considering the case, labor organizing tension across the Southeast Michigan region was growing. In Flint, a successful sitdown strike against GM had unified the United Auto Workers. The now larger and stronger union was growing in Detroit and executing rolling strikes impacting 130 factories, stores, and other businesses. 137 strikes occurred in Detroit that year–more than is recorded in any other year–and 195,000 workers participated.

The court narrowly ruled in favor of the National Labor Relations Board in a 5-4 margin upholding the Wagner Act. While Supreme Court Justices are responsible for interpreting the law, not responding to public demands, the widespread actions in Detroit, Flint, and elsewhere may have demonstrated the importance of the law and influenced its interpretation.

The Women of the Labor Movement

In many industries women, especially immigrant women, were targeted for low wage work. In the 1930’s Detroit had a number of cigar factories which targeted the Polish community, and after men had unionized, non-union Polish women new to the country. In humid factories, the women would stem, strip, bunch, and roll tobacco into cigars. Most of these factories did not offer separate spaces to eat and the working conditions caused the women to have frequent head colds, throat infections, and nausea. In June 1916, unionized men negotiated a pay raise and after years of failed advocacy for increased pay for women, the women at Lilies Cigar Company went on strike demanding as imlar pay increase. The sit down strike was also a demonstration against the intolerable working conditions, withholding pay during the first few months of employment, and sexual harassment. Within a year, their strike had spread and shut down major cigar factories in other cities. They weren’t able to accomplish all of their goals, but the women did receive a wage increase.

Detroit women led another strike at the downtown department store, Woolworth’s. One day, a saleswoman blew a whistle, and she and 99 other women sat down in a coordinated fashion at the same moment. Their demands: a 10 cent an hour raise, an eight hour work day, to be paid time and half after 48 hours of work, seniority rights, a union hiring hall, free uniforms, and no retaliation against workers after the strike. Despite the company’s threats to close, the women remained on strike for eight days. The women of Woolworth’s not only had all of their demands met, but inspired women across Detroit–waitresses at Stouffer’s restaurant, saleswomen in other department stores–and the nation to organize. It’s said that the New York City Strikes of 1937 were inspired by the women of Woolworth.

The Fair Labor Standards Act

Many of the demands Detroit’s working women were codified into law in 1938. The Fair Labor Standards Act changed wage laws by creating the right to a minimum wage, time and a half, as well as overtime pay for work over 40 hours per week–these rights are especially important for hourly workers as opposed to salaried workers. This federal law also changed child labor laws by making it illegal to employ a minor.

Myra Wolfgang: The Battling Belle of Detroit

Myra Wolfgang was a Jewish woman born in Montreal, Quebec, Canada who moved to Detroit at the age of one. By 18 she had become heavily involved in labor unions and organizing and at 23 she was elected recording secretary of Detroit’s Local 705 of the Detroit Waiters and Waitresses Union. In her work, she supported the women of Woolworth’s and those across Detroit working in department stores and hospitality. She represented workers internationally in the 1950’s as Vice President of the Hotel Employees & Restaurant Employees International Union and was actively involved in the passing of Michigan’s 1966 minimum wage law. In 1974, Myra was the inaugural chair of the Coalition of Labor Union Woman (CLUW) which had its first conference attended by 3,000 women from 82 unions nationwide. Finally, Myra was a lifelong member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and would insist on her union’s hiring hall establishing integrated crews.

The Myra Wolfgang Papers, copies of her writing and other documents from her life and work, can be found at the Walter Reuther Library of Wayne State University.

Detroit Labor Leaders Make History

There were many labor icons who came from Detroit, but here we’ll explore a few: brothers Walter, Victor, and Roy Reuther; Jimmy Hoffa; Mildred “Millie” Jeffrey; and Nelson “Jack” Edwards.

Millie Jeffrey, a Voice for Women

After multiple experiences in labor organizing in Minnesota, Philadelphia, and D.C., Mildred “Millie” Jeffrey moved to Detroit to become the first director of the UAW’s newly established Woman’s Bureau in 1944. Millie was not only the first female director of the UAW in any area but her position, and the bureau, were quickly critical for women in labor as men returned home from World War II and displaced women from manufacturing jobs. At the end of that year Millie organized the UAW Women’s conference to honor the work of women in manufacturing during the war and reaffirm the UAW’s mission to represent all of its members indiscriminately and regardless of gender. That affirmation set the foundation for the bureau, initially started under the War Policy Division, to become a permanent department of the UAW under the Fair Practices and Anti-Discrimination Division in 1946. Millie went on the run the UAW’s radio station, it’s Community Relations Division and other work within the organization. She took the national stage as a co-founder of the National Women’s Political Caucus alongside a multicultural group of seven women such as Fannie Lou Hamer, Jill Ruckelshaus, and Gloria Steinem. Among the organization’s many accomplishments, it worked to establish the Equal Rights Amendment to the United States Constitution which ended distinctions between men and women in applications of the law.

Hoffa and the Teamsters

Jimmy R. Hoffa led his first strike against Kroger for its poor working conditions and won. This act brought him to the attention of the Teamsters, a union, founded in 1903 and originally focused on workers in transportation and logistics: those who work in warehouses and deliver goods; truck drivers and packaging workers. Through the 1940’s the Teamsters had become the most powerful union in the country since it’s labor strikes could halt the delivery of essential goods. Hoffa joined the Teamsters in 1933 and continued to build influence throughout his career, including serving as Trustee on the General Executive Board in 1947, an election to the board as a Vice President in 1952 and being elected General President at the national convention in 1957.

His work had a major impact on labor nationwide especially when, in 1964, he unified all freight drivers under a single collective bargaining (wage) agreement: The National Master Freight Agreement standardized protection and benefits for more than 450,000 long haul and local shipment drivers across the country. This work significantly grew the Teamsters and further reinforced their national, and statewide, power and influence.

Nelson “Jack” Edwards”

Jack Edwards started his union work in Detroit in the 1930’s at the Chrysler Foundry Plant (foundry is the process of shaping and casting hot metal into specific shapes). Edwards’ leadership with the UAW grow from serving on the education committee of the local 600 to eventually becoming an international representative for the UAW’s westside Region 1A. In that role, he helped to further grow UAW membership by recruiting workers who drove Caterpillar machines–bulldozers and similar equipment. He served in the international representative role for 14 years. Edwards also co-founded the Trade Union Leadership Council (TULC) in 1957; the Negro American Labor Council (NALC) in 1959 (headed by A. Philip Randolph); the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists (CBTU) in September 1972. In May, 1962, Edwards became the first Black man elected to the executive board of the UAW in the role of vice president and was re-elected to that role three times.

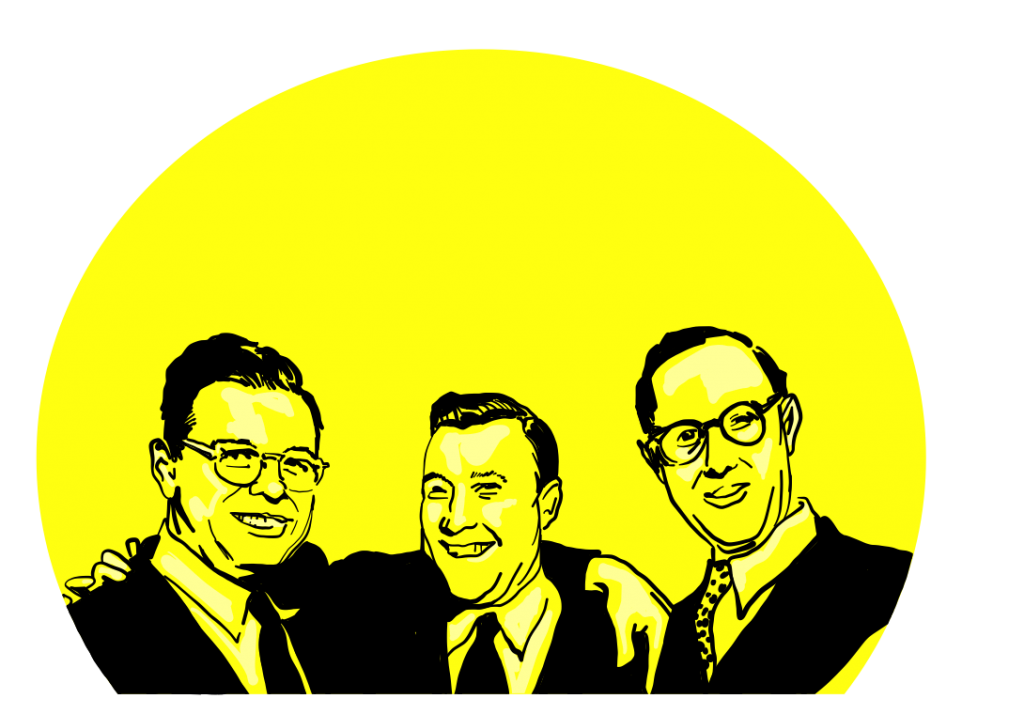

The Reuther Brothers

You may have heard the name Walter Reuther (he’s referenced in this lesson many times by the Wayne State Library Collection named for him) since he is a well-known figure in Detroit’s labor history. Reuther was not a one man show though; in fact, travelling with him on a labor organizing in their own unique ways were his brothers Victor and Roy Reuther. W. Reuther, the oldest of the brothers, moved to Detroit to attend Detroit City College (now Wayne State University) and his brothers joined him there. Their organizing began in college there demonstrating against reserve officer training on campus as well as the college’s segregated swimming pool. The labor organizing lives of the three brothers separated and intertwined throughout their lives with the UAW as the common point to which they all would return. Each of them played a role in the sit down strikes of 1936 and 1937. Victor and Walter were instrumental in the Kelsey-Hayes sit-down strike: Victor worked at the plant and organized the workers into the UAW Local 174; Walter was eventually president of that local and the workers’ representative (the person with whom management would negotiate) during the strike. Roy had just become the assistant organizing director of the UAW Flint and worked to organize the GM sit down strike there.

Walter would go on to become the UAW president in 1946 and, among other things, accomplished a historic bargain with General Motors (GM) that tied wage increases to cost of living and productivity increases–as it becomes more expensive to live in the city (e.g. overall increases in rent) and/or as the company produces more product, worker wages would increase. His leadership was deeply connected to civil rights and social welfare beliefs such as national health care and job security. Walter used his position and power to support the movements of other groups as well–he spoke at the March on Washington and marched with Cesar Chavez in California with the United Farm Workers. Victor took his labor organizing international for a time, organizing labor unions in Germany and Eastern Europe. He returned to Detroit and the UAW, serving as its Education Department Director and advocating for including women, minorities, and young people within the union and its leadership. He was eventually named the UAW’s Director of International Affairs in 1955. Roy’s work evolved toward governmental advocacy. He left the UAW for a time and served on the War Production Board as well as in the U.S. Army. When he returned to the UAW he did so ultimately as the administrative assistant to the president, his brother Walter. He also served as the director of the Citizenship-Legislative Department and directed voter registration campaigns in 1960 and 1962. That work led him to be appointed to the Presidential Commission to study state and local voter registration in 1963. The three brothers were critical to the evolution, leadership, and growth of the UAW.

The League of Revolutionary Black Workers

By now you’ve noticed that the history of labor organizing has often been to fight for equality, for some people. Much like other organizations throughout our nation, state, and city’s histories, noble intentions and work can be challenged by exclusionary practices. Labor unions have evolved in many ways to better represent people of color and women but in the 1960’s in Detroit, another organization emerged with closer ties to the fight for civil rights, growing Black militant approaches, and a determination to fight specifically on behalf of Black workers. The League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW) was founded in Detroit in 1969 and worked to unite Black workers across the auto industry and other industry sections under a banner of Black liberation, Marxist-Leninist philosophies, and increased political power. Other “revolutionary unions” had emerged earlier in the 60’s with a similar focus such as the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement and the Eldon Avenue Revolutionary Union Movement; all of these organizations joined together to form the LRBW. Its core leadership was made up of General Baker, Chuck Wooten, John Watson, Kenneth Cockrel, Mike Hamlin, and Luke Tripp. The organization’s focus on both workers rights and racial justice offered a unique space for Black workers who were experiencing discrimination and exploitation in both areas in their workplaces. Further, its work to connect with the local community through its publication Inner City Voice (edited by Watson) and youth group as well as to establish political leadership within union organizations by running and supporting candidates set the stage to connect the former civil rights movement of the 1950’s and 1960’s to the Black Power movement of the late 1960’s and 1970’s and the coinciding Black workers movement of the 1970’s.

There was even organizing for farm workers in Detroit! Mexican American Detroiter Arturo Rodriguez worked with the United Farm Workers organizing the boycotts of lettuce and grape growers in Detroit area grocery stores. His efforts, and those of his colleagues, brought 80 striking farm workers to Detroit in support of their boycott in 1973.

“Poor people can come together and improve their status in this country through organizing.”

-Arturo Rodriguez

The Forces for Civil Rights in Detroit

For Black Americans in this country there have been many iterations of the fight for civil and equal rights. From slave uprisings to the abolition movement, people have organized for freedom and justice. The 1950’s, 1960’s, and 1970’s were all critical periods for this fight; the periods’ movements and philosophies built upon one another, overlapped with one another, and in some cases contradicted one another, but all shared the same goal: liberation from oppression for Black Americans.

In Detroit, a unique city given the strong presence of labor organizations and the large population of African Americans, some forces for civil rights grew from strong roots and/or were nourished on our streets.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Visits Detroit

Did you know that Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered speeches in Detroit twice? Did you know that the first time the famous I Have a Dream Speech was delivered it was done in Detroit? On June 23, 1963, Dr. King led a Freedom March of over 125,000 people down Woodward and at Cobo Hall he within his speech he delivered these words:

“I have a dream this afternoon that one day here in Detroit, Negroes will be able to buy a house or rent a house anywhere that their money will carry them, they will be able to get a job.”

In that same speech, he also called for those fighting for civil rights in the South to help end segregation in Detroit, sending a message that connected our city to the fight across the country.

Arguably, Dr. King. is synonymous with the civil rights era –– both his booming baritone, the cadence of his words punctuated with the elegance of the Baptist pulpit, King was a remarkable figure whose movement was national in reach but his work was local; he moved from city to city learning about the challenges there and identifying opportunities to take action.

The Freedom March wasn’t King’s last time in metro Detroit. On March 14, 1968 Dr. King was invited to speak by the Grosse Pointe Human Rights Council and at Grosse Pointe South High School. He delivered his speech entitled The Other America to 2,700 people with 200 picketers outside and a number of hecklers inside. Within that speech he also expressed his opposition to the Vietnam War.

A few weeks later (on April 4), Dr. King’s voice was silenced when he was assassinated, and the nation wept. But the work continued and it continued in Detroit. Toward the end of his life Dr. King had announced The Poor Peoples Campaign (1967) and was planning another march of 2,000 people demonstrating on behalf of those experiencing poverty. He was killed before he could complete that work and it continued under Ralph Abernathy and Dr. King’s wife, Coretta. On May 13, 1968 Detroiters who were a part of the Poor People’s Campaign marched at Cobo Hall.

Many local Detroiters looked to honor Dr. King’s including Congressman John Conyers, Jr. who worked to keep King’s legacy alive, not only in Detroit, but around the world. Thanks to Conyers’s efforts (and others), the national MLK Day holiday was established and would be observed on the third Monday annually in January –– was established.

Hon. John Conyers Jr.

Hon. John Conyers, Jr. was a leading Civil Rights stalwart who impacted and promulgated progressive policies throughout his 26 terms in office

Representative John Conyers, Jr. used his power as an elected official to uplift the fight for civil rights. In addition to supporting policies that benefited those in poverty, holding review sessions on police misconduct, he notably fought for 15 years to establish MLK Jr. Day as a federal holiday. In 1983 he accomplished his goal within the Ronald Regan presidency.

And, starting in 1989 and continuing every congressional hearing until his retirement, Rep. Conyers introduced a House Resolution to “to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans.” A bill that as intended to study the historical impact of slavery on African Americans and make proposals to improve the quality of life for African Americans given that impact.

1969 Congressional Black Caucus Begins

Rep. Conyers co-founded the Congressional Black Caucus, an organization made up of the elected African American congresspeople and other congresspeople who support policy positions in support of African Americans.

Other Ties to the Movement

Rosa Parks, who eventually moved to and settled in Detroit, was hired to his staff after his 1965 election, though she had supported him the previous year. She remained on his staff until her 1988 retirement.

At the time of his death in 2019, he was the longest serving African American congressperson. At the time he was also the longest consecutively serving congressperson as well earning him the title Dean of US House of Representatives which local Detroiters affectionately shortened to The Dean. He had served from 1965 to 2017–52 years–on a platform of Jobs, Justice, Freedom.

Motown Spreads the Gospel

Detroit’s music history as the home of Motown–the company and the sound–opened the airwaves for opportunities to share messages of resistance, freedom, and peace.

Motown, Berry Gordy’s pop behemoth, whose artists dominated the airwaves in the 1960s with its “Sound of Young America,” added a spoken word label to his historic company called Black Forum which would capture speeches, poetry and other oral history on record. Dr. King’s 1963 speech would not be excluded from this. Following Dr. Kings murder, Motown went on to release a compilation of Dr. King’s major speeches titled Free at Last; it was the first record label to do so.

The Black Forum, a platform for Black intellectuals and activists to help educate the public about current events nationally also released Dr. King’s speech Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam as well as Stokely Carmichael’s 1970 speech Free Huey! (which called for the release of Black Panther Party for Self Defense co-founder Huey P. Newton). Other albums the label released include:

- Langston Hughes & Margaret Danner–Writers Of The Revolution

- Guess Who’s Coming Home: Black Fighting Men Recorded Live In Vietnam

- Ossie Davis & Bill Cosby Address The Congressional Black Caucus

- Black Spirits: Festival Of New Black Poets In America

- Imamu Amiri Baraka–It’s Nation Time: African Visionary Music

The Black Forum’s last release, Elaine Brown, was released in 1973. The fully vocal album was delivered by the woman of the same name who was an activist for prison reform and would become the only female leader of the Black Panther Party.

The music culture of the city wasn’t limited to record labels; radio stations and their hosts held down the airwaves daily and had the opportunity to use their platforms to spread local and national news, elevate individual profiles, offer social commentary and overall influence public perspectives.

On November 7, 1965, Dr. Wendell Cox and Dr. Haley Bell on November 7, 1956 launched WCHB 1440-AM— the nation’s first black-owned and operated radio station including a line up of DJ’s that set the bar for broadcasting in Detroit.

Martha Jean Steinberg, or Martha Jean the Queen, was one of those DJ’s who not only broke barriers as a woman in a male dominated field but grew to influence other radio stations and programs nationwide. The Queen started her career in 1954 at WDIA radio station in Memphis, Tennessee where she first established the expectation that their program serve and educate the community. Her 1963 move to Inkster and WCHB introduced her to the Detroit community and by the time she had moved to WJLB later that year she had established a following who looked forward to the music she played, yes, but also to her social commentary such as her afternoon “blue collar worker salute.”

In the summer of 1967, when the Detroit Uprising occurred and Detroiters were in the streets in direct conflict with police for days, The Queen stayed on air for 48 hours straight encouraging Detroiters to maintain their safety in their homes. Later, she also hosted a call in program with police commissioners to attempt to address the abusive presence of police within the community and subsequent tension.

“Black radio was God-directed for the salvation of this nation and world” – Martha Jean the Queen

Another pioneer in radio was William V. Banks, who launched Michigan’s first Black-owned FM station, 107.5 WGPR. In 1964, he worked to offer a platform for Black people to share their stories and resist inaccurate depictions in mainstream media and expand opportunities for Black people to participate in the broadcasting industry.

[Character: People don’t listen to the radio as much today since we have so many streaming services, but back then radio personalities were like youtube stars or podcast hosts. People came for the music and stayed for the DJ.]

Open platforms to share information and social commentary are critical for movements, advocacy, and social change. Many organizations created newsletters or leaflets to get information out and the opportunity to use music to facilitate information sharing was a critical component to the fight for civil rights.

Liberation on Many Fronts

Dr. King wasn’t the only leader who delivered a famous speech in Detroit. El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, or Malcolm X, visited Detroit’s King Solomon Baptist Church on April 12, 1964 and delivered the speech The Ballot or the Bullet, a speech that called for a Black people to embrace the political philosophy of Black nationalism, which as he defined in the speech meant for Black people to control the politics, politicians, and economy of Black communities. His emphasis on the political system and encouragement to participate in voter registration drives at this time was both new and influential. While some Black clergy opposed his presence delivering the speech, believing separatist beliefs to be harmful to the fight for civil rights, Malcolm’s departure from the Nation of Islam a year previously shifted his message from what it had been before. The new message of fighting for human rights and participating in the political structure demonstrated a bridge between his philosophies and those of Dr. King, whom he had previously had what was characterized as a “rivalry.”

Black nationalism has strong roots in Detroit. The religious organization Nation of Islam was founded in Detroit in 1930 by Wallace Fard Muhammad with goals to not only spread a particular religious ideology, or belief system, but also to teach and promote self-sufficiency for Black communities.

In 1956, a Christian Black nationlist congregation was established by Jaramogi Abebe Agyeman (formerly Bishop Albert B. Cleage). The Central Congregational Church of Christ, later renamed the Shrine of the Black Madonna of the Pan African Orthodox Christian Church for its historical painting of a Black Madonna holding a Black Jesus, is located on Detroit’s west side and integrated Christian religious beliefs with those of Black power and resistance. Cleage became a leader in Detroit and a confidante for other Black civil rights leaders. By the 1970’s the Shrine had five churches in Detroit, one in Kalamazoo, and missionaries travelling across the country and even to African countries sharing the theological belief system that Black people could see themselves, their struggle, and most importantly their fight for liberation within Christianity. Bishop Cleage travelled to colleges giving speeches and recruited students and other young people to move to Detroit and join the Shrine. The church is a cornerstone of the Pan-Africanist movement in Detroit, a movement which is focused on connecting Black people everywhere to the common struggle for liberation and celebration of history and culture rooted in the shared descendance from African countries. However, more than a religious institution, the Shrine was also an educational and cultural center and played a key role in politics. The Shrine’s bookstore has hosted guest speakers and events, sold cultural items and clothing and served as an overall access point for Black thought.

The Shrine’s political arm, The Black Slate, Inc. became one of the most trusted political organizations in the city and endorses candidates who support policies that are beneficial to the Black community.

More than Black and White

The 1970’s were an important time for racial liberation, organizing and pride for many groups including Latinx Detroiters and Arab Detroiters. The 1967 Rebellion did not leave Southwest Detroit untouched; residents there released their frustration as well. That paired with the rise of the Chican@ movement–a Mexican American empowerment and pride movement–led to the establishment of a Brown Berets chapter in Detroit. The chapter was small but committed to demonstrating against police brutality. In 1969, the organization Latin Americans for Social and Economic Development (LA SED) in Southwest Detroit began its youth and older adult services with support from community leaders, union officials, and, four the first four years, complete funding from the Catholic Archdiocese of Detroit. The organization provided direct services such as support for new immigrants, foster care, and referrals as well as worked as an incubator connecting the Latinx community to the broader Detroit political and business community.

The Arab Detroit community in Detroit was just as diverse then as it is today with individuals tracing their roots back to Yemen, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, and Iraq. Many Arab Americans had settled in Dearborn and Detroit near its border as well as near the automanufactoring plants where they would be employed. Arab workers were active in the labor movement with ties to the UAW and, inspired by Black revolutionary organizers, the workers established the Arab Workers Caucus of the UAW in 1973. The group of more than 2,500 workers was, in part, inspired in an effort to advocate for the UAW’s divestment from Israel during the Arab-Israeli wars of that time. Around this same time, the organization Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS) was founded by Ismael “Ish” Ahmed, Don Unis, and others. The organization started in 1971 in Dearborn to provide social services to the Arab community and facilitate the acclimation of new Arab immigrants. The organization grew over time and became a central community organization serving Arab Americans in Detroit, Dearborn and across the region.

Legal Rights

The fight of the Civil Rights Movement led to the landmark federal Civil Rights Act of 1965 which struck down segregation and the Jim Crow Laws which supported discrimination. Locally, a group of mothers was headed to the forefront of the legal rights front by taking up courtroom battles on behalf of children, families, and those experiencing poverty. The Detroit organization Westside Mothers was founded in December 1965 as a welfare rights advocacy organization. Its advocacy included issues related to public assistance, such as food stamps, Medicaid, childcare, Supplemental Security Income, and disability. It was founded by its coordinator, Selma Goode and branched off from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) where she had been organizing mothers receiving Aid for Dependent Children. The Westside Mothers quickly began to coalesce around issues of access to utilities and aid which led them to be at the forefront of litigation. They won many lawsuits on behalf of women and children including achieving an annual clothing allowance, standardizing criteria for free school lunches and prohibiting schools from using changes to lunch as a punishment for students. The Westside Mothers and their work were instrumental in creating the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization (MWRO) and the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO).

Westside Mothers

The work of the Westside Mothers continued and in 1981 they marched 100 miles to Lansing to prevent welfare payments from being cut 5 percent. They continued to fight in court over the years supporting their work with dues paid by their membership and their court battles–the wins and losses–impact services for people experiencing poverty as well as precedent for others who would fight in court. The Selma Goode papers can be found at the Walter Reuther Library.

Connecting the Dots

The fight for equality is a shared experience. Some groups have had to work harder to secure the American dream as promised in the Declaration of Independence and later, in the nation’s founding document, the Constitution. The fight for equal rights has been shaped and remolded over time. The labor movements and civil rights demands took on a new shape compared to the engagement of the past and the fight has taken on new shapes still as time has gone on. What we’ve done here in Detroit has inspired and left its own imprint on the shape of the fight for equal rights locally and nationally.

Lesson Review

Write a short essay exploring the following questions: 1) How are the labor and civil rights movements connected? 2) Why are they important for Detroit?