Communities reflect their leadership; both the people with the titles, such as the mayor, and the people who participate in the civic engagement process, those who lead together to represent us and our neighborhood. The success of communities is partially due to the active citizenry within a democracy, but also the leadership on display by our elected officials whose jobs are to not only listen to the “will of the people,” but to effect change by informed decision-making and by extension, effective leadership.

In 2014, a common phrase emerged describing the development of the city: “two Detroits.” Downtown’s business and entertainment development was growing supported by partnerships between Mayor Mike Duggan and the business community–big businesses like Quicken Loans and the Ilitch Holdings, Inc. as well as the entrepreneur community. Neighborhood services were slowly expanding and improving but as downtown attracted more city visitors and residential areas still suffered from blight and slow service response times, many community members questioned the Mayor and his administration’s priorities.

The phrase was coined in 2014 for a new generation but it was not the first time such a criticism had been levied or such a conflict presented itself in the Detroit community between residential versus downtown development. Mayor Coleman A. Young, who served from 1974 to 1994 faced the same criticism as he erected the Renaissance Center in 1977 and fought for other downtown business development. Both mayors did work to improve city services as well, and Mayor Young would go on to be a favored mayor in Detroit history but how community members characterize their values, needs and priorities as well as how they perceive the values, initiatives, and leadership of elected officials impacts how our city develops and changes all the way from our blocks to the structure of our local government.

In this lesson we will explore how changes in leadership have the potential to impact, and change, the city, and how some of Detroit’s leaders helped to shape the D, as we know it today.

Representation and Leadership

The individuals who hold leadership positions each have their own styles, values, and goals. The structures within which they hold their positions determine how they are set up to execute their goals as leaders.

The city of Detroit has seen changes to its government structure over the years. The City Charter (which you’ll learn all about in How Does Local Government in Detroit Serve Us?) establishes the structure of Detroit’s government and can be amended or revised periodically. City leadership can also make decisions about certain departments and their functions, as well as budgets which impact how leadership can be put into action in those areas.

One area that has faced multiple changes is Detroit’s education system. Up until 1949, the public school system was a part of the city of Detroit budget and the mayor was the president of the board of education serving alongside the city recorder and elected “inspectors” from wards of the city. From the inception of the public school system in the 1800’s through the early 20th century, the size of the board of education fluctuated and even had up to 21 members selected from different parts of the city. However, the mayor and city council retained the most power over the school system and its budget. After 1949, public schools were able to operate independently of the city with an elected board. In 1969 representation changed again; state law required the district to be decentralized. Eight regions were established each with boards overseeing the schools within them and a centralized board made up of members from each region was also established. In 1981, voters elected to do away with the regional boards and go back to a single school board. Fast forward to 2009 and leadership changed again. Governor Granholm declared DPS to be in a state of financial emergency and appointed an emergency manager to be responsible for the financial operations of the district. The individual holding that role would change various times in the seven years the district was under emergency management. During that time the elected board did not have power over the district’s financial operations and emergency managers as appointed officials did not have official accountability to community members. Finally, in 2016 emergency management ended and a new election occurred with a newly empowered school board responsible for both academics and finances. So, you can see how the changes in elected leadership also change who has the ability to represent Detroiters.

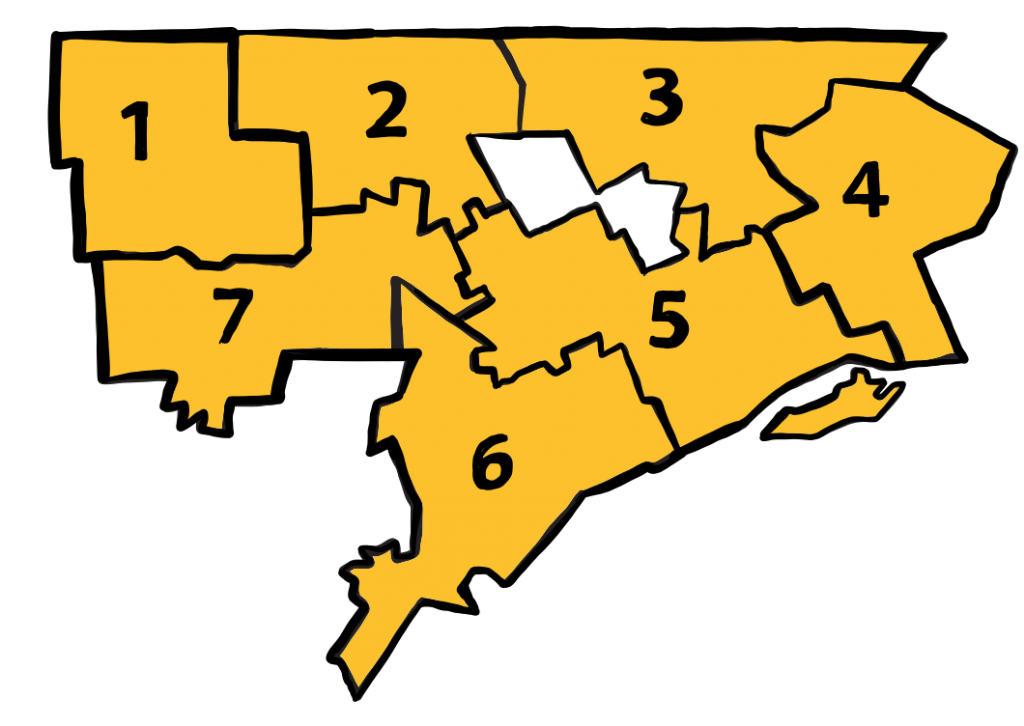

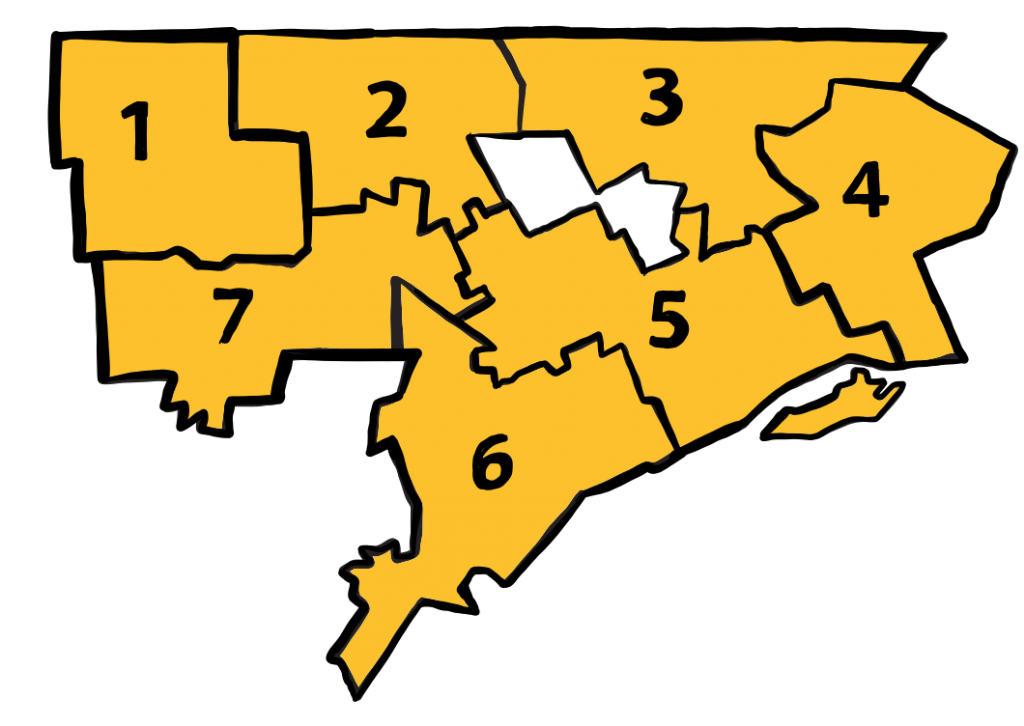

Detroit’s City Council is another example. The powers of City Council collectively, or individually to each member have changed through the years and with new city Charters. Prior to the 1918 Charter, Detroit had a 42 person ward based legislature which spread out its powers. Following it, council people were elected at-large, meaning individuals ran for office to represent every Detroiter in the city. The 2012 Charter changed things again, requiring that City Council take more oversight of Mayoral appointments, enlarging independent departments (giving Council more say in their operations), and restructuring city council to be made up of one individual elected from seven districts and two elected at-large (representing the whole city).

Courts Made More Impartial

Erma Henderson served on the Detroit City Council from 1972-88 and was council president for 12 years. She was the first black woman to be elected and to be council president. Prior to her election, in 1970, she worked with the Equal Justice Coalition helping to train their “court watchers” who attended the Recorder’s Court and tracked the disparate treatment of Black and poor defendants. The Recorder’s Court, which was merged into the Wayne County Circuit Court, heard cases for ordinance and traffic violations as well as felonies.

Court Watcher’s findings:

- With a lawyer, 62.3% of Black people still plead guilty; 34.7% of white people plead guilty

- African Americans were sentenced to jail as opposed to a fine twice as often as White defendants

- In the absence of an attorney, bail was set at below $1,000 for 41.7% of white defendants and above $1,000 for 72.6% African American defendants

- Jail sentences were most likely for those wearing work clothes and least likely for those wearing a suit and tie

The observations made by the court watchers were made public in a report and helped to make the case for a new courthouse, the Frank Murphy Hall of Justice, as well as new court practices such as ensuring privacy for defendants to speak with their lawyers and fee schedules (set fees amounts). After the reports release, there was a significant change to disparate sentencing.

Finally, community leaders can impact representation as well. The TULC was founded in 1957 by Horace Sheffield and Robert “Buddy” Battle to increase Black representation in the Union of Autoworkers (UAW) and union movement as a whole. However, the TULC also showed their larger civic power by mobilizing the Black vote in Detroit and supporting surprising victor Jerome Cavanaugh for Mayor in 1961. Today, elections in Detroit can be highly influenced by local organizations’ “slates.” Trusted community organizations like the Black Slate, Fannie Lou Hamer, labor organizations, and the local congressional district organizations evaluate candidates who are running for office, select those that they think best represent their values and will be allies then promote them all together leading up to the election. The support of these organizations and their work to get the word out impacts the opinions and choices of voting Detroiters.

The Reflection of Racism in Detroit

We may think Detroit of slavery free city because of its connection to the underground railroad, but slavery did exist in our city of the 1700’s and 1800’s. The fur trade, with roots in the city’s French origins and Canadian ties, dominated the culture of the city and with it came the enslavement of Indigenous peoples. African American slaves and indentured servants lived in Detroit as well but in smaller numbers than those who were Indigenous. Despite treaties and agreements outlawing slavery, the practice continued in the city even within the household of Detrot’s first mayor, John R. Williams.

How strange might it have been for a fugitive slave, having heard that the north and Detroit was a free territory only to arrive and learn that not only could they be at risk of slave catchers but also the city was not as “progressive” as rumor would have it?

Another moment with a direct connection between city leadership and racial discrimination occurred in 1930. Mayor Charles Bowles’ as a candidate showed support for the Klu Klux Klan which helped him to win enough votes to become mayor. In the end, Detroiters were not impressed with his city management and recalled him less than a year later. The recall was not based upon his relationship with a hate group but on his performance in his municipal duties.

It could be argued that the KKK and other hate based organizations were emboldened by Bowles’ victory in the ensuing years. The Black Legion, which in its origins was a part of the KKK, established a chapter in Highland Park in 1931. It was a widespread secret society perpetuating violence and hate against Black, Catholic, and Jewish Detroiters as and had many members within City Government. The Black Legion in the 1930’s:

- Killed four known people (and was suspected of many more)

- Had over 20,000 members in Detroit in 1935

- Had members iInside of government including the Detroit Public Lighting Department, the Detroit Police Department, and the Department of Street Railways

Did You Know?

Heinrich Pickert took over as Police Commissioner in 1934 and was likely a member of the Black Legion. However, Mayor Frank Couzens, who served from 1933-1938, pushed to eradicate them all, and suspected members were suspended.

Race and racism in Detroit’s leadership would continue to be a prominent issue as the city’s story continued to unfold and the population became increasingly African American.

Conflict and Change

Mayor Cavanaugh, a mayor who joined the Detroit March for Freedom in 1963, also led an administration during a time of increased racial tension. His administration inherited the continued racial tension sourcing from the growing Black population and segregation fueled conflict. For example, the community had been deeply impacted by the 1943 Race Riot that started on Belle Isle. The riot began as a reaction to parallel rumours within the Black and white communities. White Detroiters rumoured that a white woman had been assaulted by Black men and Black Detroiters rumoured that a Black woman had been assaulted by white Detroiters.

Nearer to his administration, segregated neighborhoods and business districts generated conflict and city high school students were demonstrating against racism in their schools. And Detroit’s majority white police force was perpetuating racism, abuse of power, and brutality in Detroit’s communities. Detroit reached a boiling point during the Cavanaugh administration when police officers raided the Blind Pig bar on 12th and Clairmount.

After years of police harassment, racist employment practices in Detroit, and segregationist housing, frustration was high among Black Detroiters and the raid on the Blind Pig, in the congested Virginia Park area, became a point of release for the frustration. A crowd gathered protesting the raid and subsequent arrests; that same crowd began to physically confront officers and the 1967 Rebellion was sparked.

Police Factors

Detroit Police Department factors leading to the rebellion:

- A 97% white police force in a 40% black city (1965)

- The “Big Four” Police officers unit regularly assault Black residents for little to no reason across the city

- No police officers convicted in any civilian killings

- Police Commissioner (Chief) Edwards says 90% of his Police force is bigoted and “a dislike for negroes is reflected constantly in their language and often in their physical abuse”

The rebellion began on July 23, 1967 and lasted for five days. 43 people died during that period; 33 were Black and 10 were white. 7,000 people were arrested and more than 1,000 buildings were burned. The leadership of the city and state at that time determined how those five days were handled: the Governor Romney sent in the state police and national guard, Mayor Cavenaugh requested a media blackout the first day, Black community leaders and elected officials worked to calm the community, and many people worked together to determine how to address the unrest.

The discontent that had built up between the black community and the police department reverberated past July 28, 1967. Detroiters fell into two minds about those five days of summer: that its root was in the consistent harassment by the police towards black Detroiters or that it showed the need for greater policing and lawfulness.

Mayor Cavenaugh, who had been building a progressive reputation leading up to the rebellion decided not to run for re-election. Mayor Roman Gribbs defeated candidate Richard Austin in 1969 by only 7,000 votes or 1.5% of the vote with a belief in increased policing leading to the establishment of the notorious decoy unit Stop The Robberies Enjoy Safe Streets (S.T.R.E.S.S).

The S.T.R.E.S.S. unit killed 22 Black Detroiters in its decoy operations including a Black Wayne County Sheriff Deputy, Henry Henderson. The city’s Black community organized alongside existing white allies against the continued policy brutality and the city administration which facilitated it. Activists like Attorney Ken Cockrel took on the leadership through the courts by using criminal cases against Black men as opportunities to paint the picture of police brutality and murder in the community.

Moreover, this same issue defined the next election for the leader of Detroit. Coleman A. Young, a former labor organizer, faced off against Police Commissioner John Nichols. A symbolic competition between valuing community organizing versus community policing. This time it was Young who won by roughly 7,000 votes or 1.5% of the vote and under his leadership the S.T.R.E.S.S. unit was abolished and police tactics changed. After decades of racial tension and conflict the first Black mayor was elected and went on to serve for five consecutive terms.

| 1969 Mayoral Election | 1973 Mayoral Election |

|---|---|

| Roman Gribbs 50.7% | Coleman A. Young 50.3% |

| Richard Austin 49.3% | John Nicols 49.7% |

Change from the Inside

Isaiah “Ike” McKinnon joined the police force as a young man in the 1960’s. He said he was inspired to become a police officer because of seeing the Big Four abuse people in his neighborhood and after having been physically assaulted by them himself. He faced discrimination as one of few Black people on the force but rose to become Chief of Police and Deputy Mayor. His leadership was inspired by a desire to create change.

You can hear an interview with Chief McKinnon about his life and being a police officer during the summer of 1967 on the Michigan Radio Show Stateside.

Mayor’s always stand at the forefront of managing conflict and change of a city but they don’t do so alone. In addition to their work with their colleagues on city council, there are other stakeholders with an interest in the city’s future and the resources to have leadership in building it.

Philanthropy in 21st Century Detroit

The philanthropic community includes major foundations which grant programming and other funding dollars to initiatives in the city. It is common for large urban cities like Detroit to have a large philanthropic community with influence in government, policy, and social services. Detroit is unique however, in that it’s financial challenges over the years positioned philanthropies to have more leadership than is typical.

Organizations like Detroit Future City (DFC) stepped in, with funding from the Kresge Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and others, as well as a cross-sector steering committee to support city planning when the department was non-functional after budget challenges. Born from the Detroit Works planning project by Mayor Dave Bing in 2010, DFC spent two years engaging Detroit’s community and conducting research before unleashing a massive 300+ page Strategic Framework for Detroit’s planning purposes in 2012.

The Skillman Foundation which has a mission to support children and youth also became a neighborhood developer with its Good Neighborhoods Initiative–a 10 year plan launched in 2006 that supported programming and development in seven neighborhoods–and funding for community blight projects as well as moved to the forefront of education policy advocating for public policy and funding organizations that evaluate schools for example .

The Knight Foundation increased the amount of public art, beautification projects, and opportunities for local artists to gain exposure in the city and around the country as well as supported community civic development. Opportunities like the annual Knight Arts Challenge which started in 2013 and the Knight Cities Challenge offered the opportunity for anyone–individuals and organizations–to pitch their projects in those respective areas for funding.

The philanthropic presence in city development lead to both support and access to capital for local community projects and improvements but it also led to conflicts between local communities, the charitable organizations, and the city (which partnered with those organizations) over things like neighborhood names and boundaries as well as the selection of projects for funding and community leaders for those projects.

City Finances

The year 2013 was a pivotal one for Detroit; one that made national headlines and changed the city and that furthered positioned philanthropic organizations as leaders within Detroit.

During the 2013 municipal bankruptcy of Detroit, it was announced that the Detroit Institute of Art’s (DIA) artwork would be assessed for possible liquidation to pay the city’s debts. This led to shock and opposition amongst Detroit’s philanthropic, business and civic leadership. After the Ford Foundation, Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan and others offered the resources to save the artwork, U.S. District Judge Gerald Rosen along with state legislators, the mayor and city council, developed an idea for a “Grand Bargain.” This effort relied upon $366 Million from the philanthropic community, $100 Million from the DIA, $350 Million from the State of Michigan, and 4.5% in cuts to the retiree benefits of city workers and unions (which equated to about $12.1 Billion over time).

In the Grand Bargain, the city of Detroit relinquished its ownership of the Detroit Institute of Arts building and its artwork. The Founders Society, a charity board that supported the DIA, merged into the DIA and the museum wholly became independent and is now owned by a charitable trust.

Philanthropic organizations in their traditional definitions are organizations that rely on donated funds to support social causes. Detroit’s bankruptcy showed the position these organizations can also hold in policymaking when they have developed strong ties to city and state government and taken on leadership roles within city development. They weren’t the only contributors, but their support allowed the city and museum to leverage more funding and helped to facilitate partnership with the state government.

Leaders Cannot Be Separated from “the People”

We’ve reviewed political leadership, community leadership, and philanthropic leadership in Detroit over the years. It’s important to recognize that leadership is defined by influence. Leaders include the individuals and organizations that are able to influence our government, our communities, and other leaders. The values and priorities of city leaders manifest in the polices, practices, and even the culture of the city. And, the values and priorities of elected leaders reflect those of the people whose vote elected them to office. Thus, changes in leadership are both symbolic and representative of our city and its residents.

Lesson Review

Choose a local leader you know. They could be a school principal, a block club leader, an elected official, or even a parent. For this exercise, a leader is someone who is responsible for making decisions on behalf of others. Interview them and summarize your discussion. Ask what they think is the most important thing about leadership and to tell you about a time they changed their leadership–a project or an initiative they were directing; an approach, or a way of thinking–based on new information. How did they evaluate the information, what made them change?