Detroit’s Path to the Historic 2013 Bankruptcy

Background: The Perfect Storm

Cities collect revenue from tax sources such as those levied against properties or taken out of income as well as from fines and fees plus sales (of land and assets) among other areas. Cities spend money on direct services, as well as on fixed expenses that can be mostly invisible to their residents, meaning the amount to be spent is set and cant be changed by city officials. Those costs can be especially high and include for example, court settlements/legal expenses, debt payments, and pensions.

| Key Revenue | Key Expenses |

| Property Taxes-taxes from individuals’ homes and business properties. The amount collected is based upon the property value. | Pensions/Health Care-employees pay into a pension system for retirement and the city contributes as well then pays out of that system to retirees as they retire |

| State-shared revenue-the state allocates a portion of certain tax revenue, like sales tax, to cities | Infrastructure Debt-bonds and other borrowing used for city systems like water |

| Casino Taxes-Casinos pay taxes to operate in the city | City maintenance and services- buildings and properties; garbage; roads, etc. |

| What’s Bankruptcy? Bankruptcy is a last resort legal process that individuals, companies, and cities can go through when they are unable to pay their debts. Municipal bankruptcy, when cities file for bankruptcy, offers court protection when a city is in financial crisis so that basic government functions can continue while government officials work to create a plan to address the debt. |

Impossible Decisions

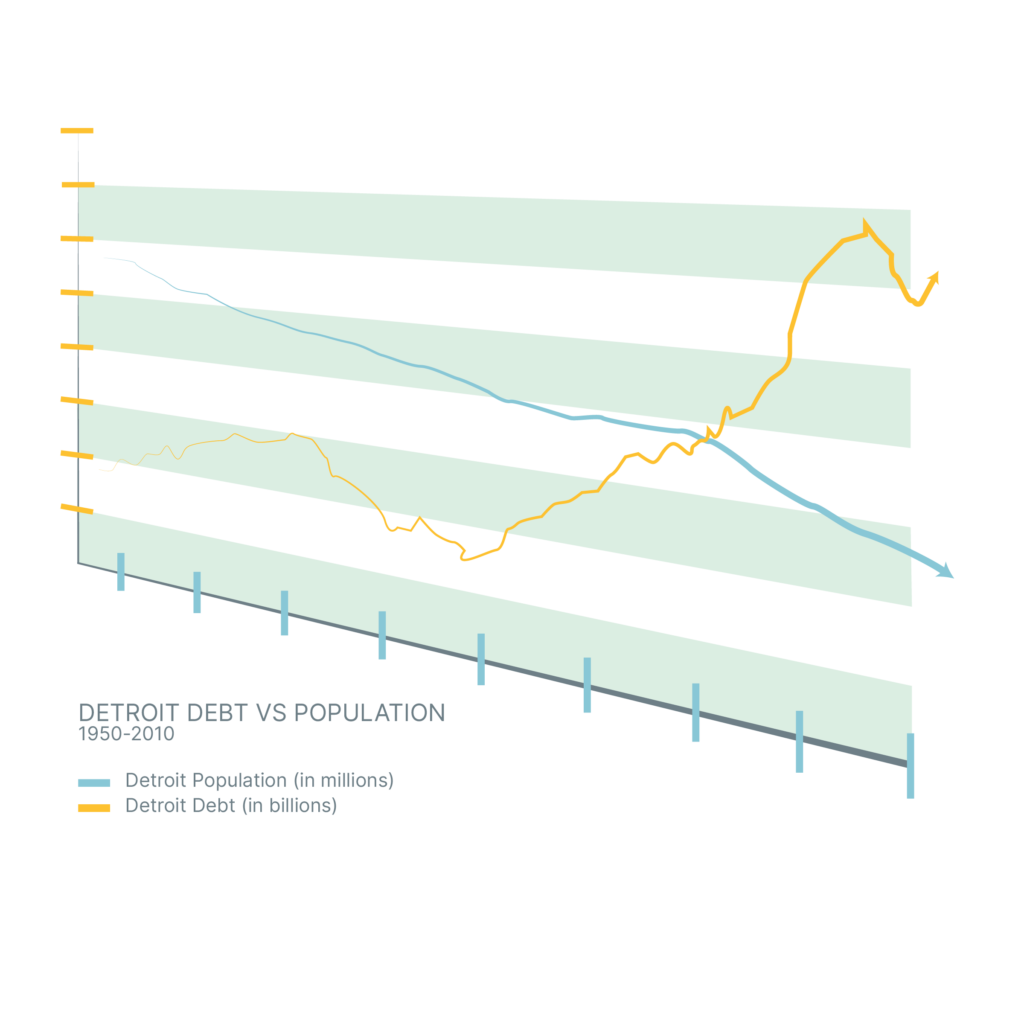

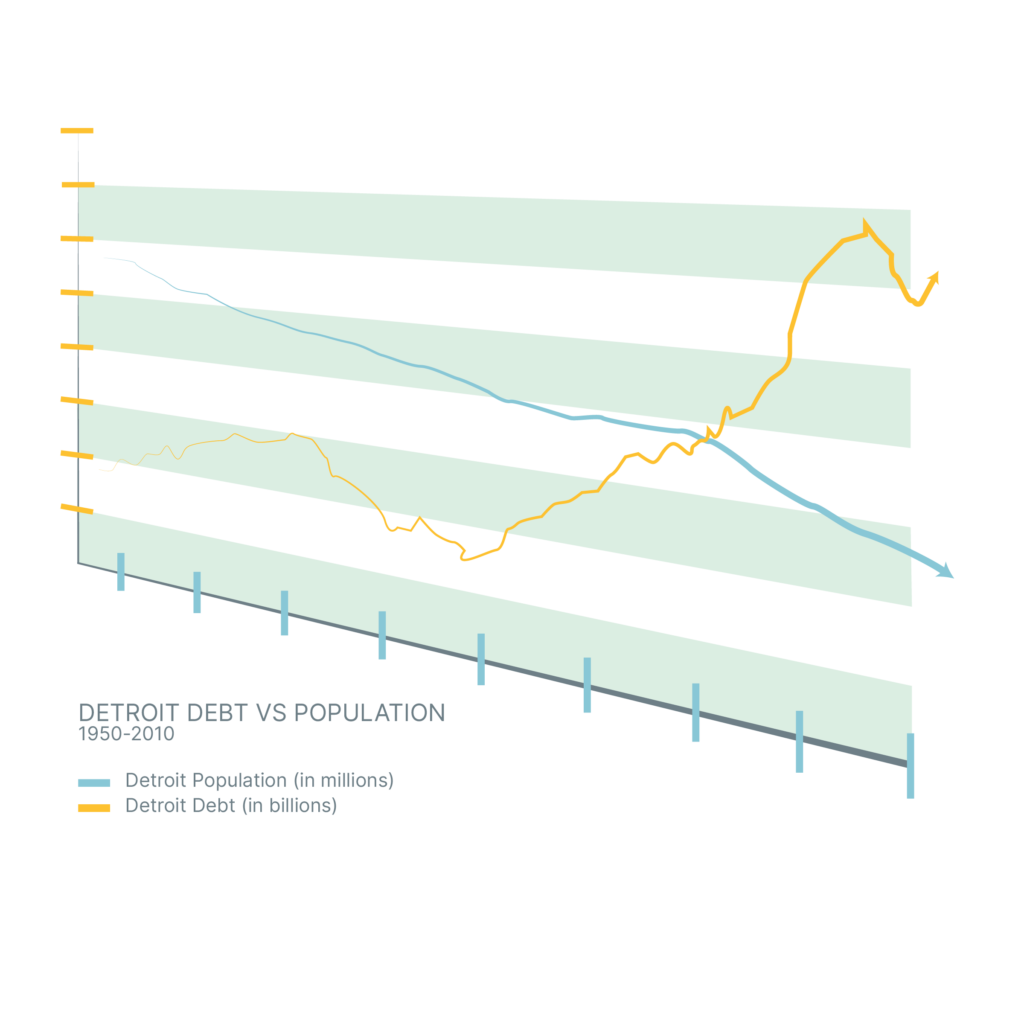

Numerous factors over many years brought Detroit to the point of bankruptcy. At its simplest, for years the city was not collecting enough money to cover what needed to be spent. The causes for this imbalance included a shrunken tax base due to urban flight (the rapid moving of people out of urban areas) along with the impact and required maintenance of the abandoned properties left behind. Aging housing created a dramatic plunge in assessed property values and therefore decreased property tax revenue. However, the service expenses of maintaining a huge, 139-square-mile city remained along with any existing fixed expenses. Still, city leaders had to make decisions about how to maintain population, as well as, grow population and investment to generate the revenue needed to cover its expenses.

City debt doubled between 1960 and 2012 but the majority of the increased debt was on improvements to the water and sewerage system and to restructure the city pension debt. Other borrowing was used to fill budget holes but absent new revenue that created a system of continued borrowing to then fill budget holes as well as make payments on debt from the borrowing: a vicious cycle.

Detroit grew very quickly in the first half of the 20th century with the arrival of the automobile industry, and then shrank in recent decades at a similarly remarkable pace. In 1950, the city had 1.8 million people; in 2013, following a pattern of disinvestment and deindustrialization, it was home to 700,000 people as well as to tens of thousands of abandoned buildings, vacant lots and unlit streets. Mayors and councilpeople had to find ways to react to the fast changes while inheriting the challenges of previous administrations.

Collecting and Spending Over Time

- Mayors Jerome Cavanagh and Roman Gribbs maintained a large workforce 1960’s and early 1970’s as the population continued it’s drop from the 1950’s and property values began to drop

- Mayor Coleman Young cut spending by shrinking the workforce and city departments during his terms (1974-1994) and increased revenue with more taxes; Mayor Young grew city income to be greater than debt

- After 1991, the number of city pensioners outnumbered city employees eventually by 2 to 1 meaning city debts to retirees were extremely high

- Mayor Archer inherited the challenging pension system which included the use of surplus earnings directly to employees and pensioners as opposed to reinvesting in the pension system (and thus supporting the debt). He attempted to change the system but was blocked

- Mayor Archer, using grant dollars, added 1,100 employees (mostly police) in the 1990’s when the city was flush but still losing population.

- Lansing politicians reduced Detroit’s state-shared revenue by 48% from 1998 to 2012, withholding $172 million from the city, according to state records.

- Mayor Kilptrack creates a two tiered system to borrow money for employee pension debt; the system results in two sums of money owed, one for each system

- Locked into the cycle, Mayor Bing continued to borrow to cover operating expenses

Government Offices that Facilitate these Decisions

- The State of Michigan: city budgets are accountable to state elected officials and per state law, should not be approved if they are not balanced

- Mayor’s Office: Detroit’s mayors, working with the budget department and other staff, develop the recommended budget each year and negotiate city borrowing

- City Council: Mayoral budgets cannot move forward without council approval; council may also make amendments to the budget

After years of increased debt the city ran out of money to pay its debt and its operating expenses. Detroit filed for bankruptcy on July 18, 2013*, the largest municipal bankruptcy filing in American history in terms of debt. Governor Snyder’s office has said the debt was likely to be $18 billion and perhaps as much as $20 billion.

*Detroit exited bankruptcy in 2014 and its budgets were subject to the approval of a State Financial Review commission for as long as required to accomplish three consecutive years of balanced budgets. The city accomplished this in 2018.

Questions

- How do changing city administrations impact how the city collects and spends money?

- Why is population size important for a city budget?